China’s Soft and Sharp Power Strategies in Southeast Asia Accelerating, But Are They Having an Impact?

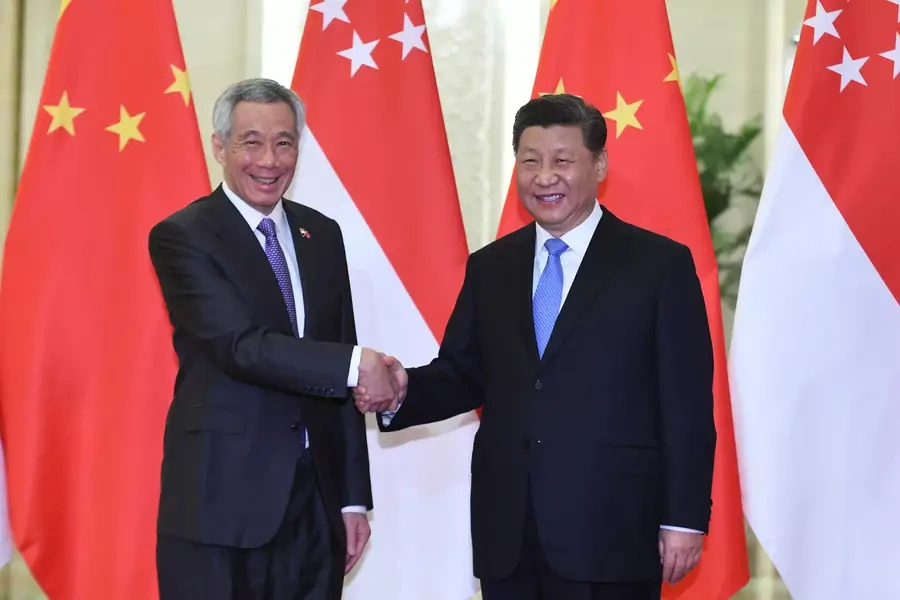

In a recent analysis for the Jamestown Foundation, Russell Hsiao of the Global Taiwan Institute presented a thorough and compelling case of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) influence operations in Singapore. Singapore is a critical state for China in Southeast Asia, given the outsized role Singapore plays in regional diplomacy, the fact that it is the only Southeast Asian state with a majority ethnic Chinese population, and the fact that its leaders have an increasingly wary approach to China’s regional assertiveness. Hsiao notes that Singapore long has been a target of Chinese influence activities, through the United Front, through business associations, through clan associations, through Chinese influence over some Chinese-language Singapore media properties, and through other tools.

His documentation is thorough, and it notes that, in recent years, China has utilized its influence at times of high Singapore-Beijing tensions, including, as he notes, one critical recent spat:

One example was seen in 2016–2017, in which nine Singaporean military armored vehicles used for training in Taiwan were impounded during passage through Hong Kong. Singapore-PRC relations were strained by the incident, but Singaporean Chinese businessmen, who held ties with government officials through grassroots associations and other channels, reportedly provided ‘feedback’ to the government to avoid stirring up trouble with China by continuing to train in Taiwan.

More on:

But what Hsiao does not explore is the extent to which, in recent years, Chinese attempts to influence Singapore seem to have grown, even compared to the long history of CCP influence strategies in the city-state. These efforts include both soft and sharp power. Singaporean officials believe that Beijing’s efforts to pressure Singaporean Chinese media, despite tough Singaporean media regulations, have increased in the past decade. They further believe that Beijing is boosting attempts to wield influence over universities and think tanks in Singapore; and, they believe that China is expanding people-to-people exchanges, which are tools of both soft and, potentially, sharp power in Singapore. There are further worries among Singaporean leaders that Beijing could increasingly affect Singaporeans’ news consumption and views of regional relations as WeChat becomes even more ubiquitous regionally as a source of conversation and information.

And is Beijing’s approach working? In some cases, like the impoundment of the Singapore armored vehicles, China’s influence approach in Singapore may have worked for China. But overall, it remains unclear whether China’s soft and sharp power approaches to the city-state are actually producing a Singaporean populace with more favorable views of China, an environment in Singapore that would make the city-state more willing to go along with Chinese foreign policy aims, or really any shift in the receiving state (Singapore)’s long-term views because of China’s actions. In fact, Chinese influence activities have sparked Singapore to have a tough, open conversation about Beijing’s efforts, and to increasingly improve Singapore’s defenses against influence operations.

Singapore, though, is not unique—and other Southeast Asian states are not as prepared as the city-state to evaluate and combat Chinese soft and sharp power strategies. Chinese influence activities are expanding in other Southeast Asian states, as China ramps up both its soft and sharp power approach to the region. In some Southeast Asian states, like Cambodia, the influence is increasingly obvious; Beijing has helped launch a news outlet in Cambodia that appears to be essentially a pro-regime and pro-China tool, and China may have played a role in manipulating Cambodia’s information environment prior to last year’s elections, where Hun Sen took complete control of the country. In other states in the region, too, Chinese soft and sharp power campaigns have dramatically increased in the past decade. I will examine these soft and sharp power efforts in other Southeast Asian states—and whether they are working—more fully in coming blog posts and other longer publications.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store